Roman table to a King’s table: How it was done and the ways to recreate the look and taste.

By

Honorable Lady Sosha Lyon’s O’Rourke

Peacock

A dish to grace the table of Kings

By

Honorable Lady Sosha Lyon’s O’Rourke

“Peacock: you admire him, often he spreads his jewel-encrusted tail. How can you, unfeeling man, hand this creature over to the cook?” (Mart.XIII-1XX/Faas, pp. 295)

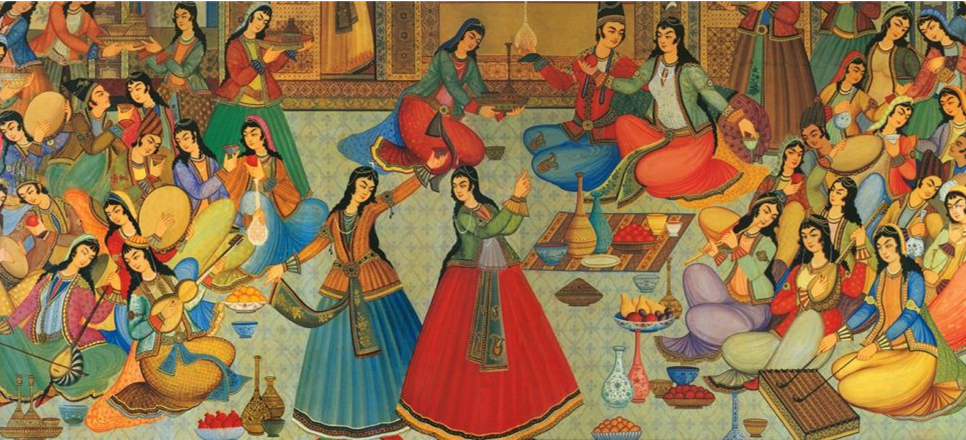

Peacocks were valued throughout history; not only for their feathers nor for their flesh. Poems and songs were written about these gorgeous feather fowls and their likeness graced plates, vases and even thrones. They represented different ecclesiastic values to different religions. This one bird, with its jeweled eyed tail, was coveted for both the look and symbolism represented in the display of this majestic fowl. From a throne in India to the table of rich Romans to the Persian Empire decorating paintings and vases; even to the table of English royalty, each used this favored bird in recipes and decoration.

“Such subtle creations could be comprised of just the edible, or as the more elaborate a set up became, a combination of paper mache and lumber to support a larger and even grander display. These decorative subtleties were for powerful displays and less about eating, with the production being undertaken by carpenters, metals smiths and painters and very little with chefs.” (www.reference.com/browse/subtlety)

This is a research paper on cooking a beautiful period dish served to royalty. It covers the trials and tribulations needed to make this display happen in today’s modern world, which lacks an availability of peacocks, as well as the “work-arounds” needed to display the dish in a mostly period manner.

Display:

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:V%C5%93u_du_faisan.jpg)

Toussaint-Samat recounts how the noble peacock was served at the Banquet of the Pheasant held in 1453. As per tradition of the time, when the peacock was served in all of its glory, the hero of the feast was to make a vow. The hero for this particular feast was Duke Phillip the Good. His vow was to challenge the Sultan to single combat. The commentary went on to say that while the vow was made solemnly it was not take seriously. (pp. 84).

Another display was “[w]hen the peacock was all arrayed in his pride, royal trumpeters blowing on silver horns or other musicians making “Sweet Musick” [sic], led the way to the banqueting hall followed by the First Lady carrying the peacock and then by a bevy of maidens clad in white…The platter on which it rested could either be of gold or silver…” (Craig, pp. 158).

As mentioned, the peacock was forced back into as natural a form as possible during cooking. Gilding of the feathers, feet and beak were done. Some gilding was done in actual gold while others were in a flour paste colored with saffron, depending on the host’s monetary status. (Toussaint-Samat, pp. 84). For displaying the dish I have run into a few unique issues, the first being the cost of the actual peacock. While researching how to cook and serve peacocks, I came to the horrible realization that full grown peacocks are EXPENSIVE. I cannot stress this reality enough. One male peacock can be priced as low as $150 (if they are very young, i.e.8-9 months or younger and without plumage) or can run up to $600 for a full grown fowl with plumage. Peahens can cost $150 for a young bird. These prices are for live birds. If the meat were desired, skinned and dressed without feathers, the body runs $300 at regular price and $200 on sale. This is without the skin and feathers. In today’s market, purchasing an actual peacock becomes difficult.

My choice, if I decided on a live bird, would have been to pay for a young bird and raise it (barring any wildlife getting tasty thoughts of their own about my peacock), then skinning and dressing it for the table. Assuming I did not damage the skin while skinning or ruin the meat by piercing the gall bladder (rendering the meat bitter and useless) while dressing out the bird, I would have had a viable solution. Unfortunately, while I have helped slaughter chickens for the table quite a few years ago, skinning and dressing were left to my dad, amid comments about not wanting to let a kid ruin dinner or something similar.

This left me inadequately skilled for raising, skinning, and dressing out a very expensive peacock. With that in mind, I have followed the Roman mindset that meat could be dressed as another meat and served forth as a “Faux Peacock”. I wanted an uncommon bird, but something well within the affordable range that could be purchased without having to special order. After weighing my options, I decided to use duck. Duck is not a lean meat with the skin on. However, the selling point, unlike a chicken, is that the duck is about the same amount of dark meat per body while commercial chickens are more breast heavy than any peacock could ever be. Duck can be rendered less fatty by the removal of the skin and can still be considered an uncommon dinner dish by most standards today. Duck was, for me, the logical substitute in my meat portion of the cooking.

Chicken was never an option, which left me with fewer choices than expected for modern dark meat. Pigeon could have been an option; however, having no hunting license pigeon and quail (being much too small to start with) were not viable substitutes. Pheasant could have been used. There were two issues for using the actual cousin of the peacock. Pheasants, for decent pricing, require a hunting license and a lease to hunt on. I have neither the weapon nor the skill to shoot. Pheasant is also not an easily attainable meat which makes pricing difficult. Each option was weighed with pros and cons, and the most viable choice again was duck. What I would pay for one pheasant, I could purchase four ducks. Duck is an all dark meat. Without its skin, the flesh can be suitably larded to imitate (not in flavor) the look of peacock dark meat.

Dressing a Peacock:

Dressing of a peacock usually comes after the cooking. The meat and cooking part was easily worked through, though the display was a bit of an issue, hence the dressing before the cooking.

See above for the cost of a live male peacock in full feathered display, making the idea of raising a peacock un doable at this time, meaning a skin would have to be purchased. I was able to find a company that dealt exotic skins; however there was a catch to the peacock skin. The skin would only be available if and only if someone brought one in and then it was a three month waiting period while the skin was treated. The price associated with obtaining a skin this way was almost unbelievable. I was able to negotiate the purchase of a skin after the seller asked what I would be using it for. The caveat by the seller was that the skin was missing a head. I didn’t have any other options or sellers at this point so the answer was a resounding “Yep! I can work with a headless peacock skin.” I did not mention my desperation at this point for any skin with feathers that could be painted to look like a peacock if I had to.

Period-wise I would have had a skin and body that would not need such subtlety in body forming or a wood carver who could shape a block of would in a simulation worthy of Henry the VIII’s table.

The skin arrived, headless as advertised and cured in such a way I would shudder dressing any bird meat in it.

The skin was beautiful, but not useful for an edible concoction due to the preservation techniques on the underside.

This abolished any idea of redressing a duck with the peacock skin and gilding the duck bill. Nor would I be able to re-stuff the skin with small birds or savory meats. (Toussaint-Samat). I thought of making a cloth body with a batting neck before realizing that sagging would take this proud bird skin and turn it into a saggy pillow of pretty feathers. Nor did I trust my carving skills (I am totally deficient in this area) for making a peacock body and head out of wood. I had to resort to artisans skilled in this area modernly.

With this new hurdle, I researched different ways in which a peacock could be displayed. The best modern equivalent I could find was from a taxidermy form. This took some work as not every taxidermy shop is considered equal no matter how much they talk about exotic birds in their bio line. The form arrived in pieces minus the head. Luckily for me the head arrived the next day.

Peacocks do not like giving up their heads even in resin form! This jigsaw of body, neck and eventually head had to be metal tabbed and glued together. Insert neck B into resin body A and no up or down listed on the body on where pieces went. Once the pieces were attached in the correct body part, glue was used to keep them from drooping or falling off. I couldn’t have the peacock losing its head again!

The head was attached to the neck with metal and glue after drilling a small hole into the head. The head was of a different and much harder material then the neck and could not have the metal bar section of the neck inserted as the neck’s lower tab was inserted into the body. That would have made life way to easy!

The next step was to wipe the form clean of dust and apply the gilding. Gold leaf would have been used or a flour paste colored with saffron depending on the serving nobilities’ financial means. (Toussaint-Samat, pp. 84) My first attempt with gold leaf was a disaster. Uneven, splotchy, and just ugly are the words I would use to describe this decorating application. After removing my gold leaf disaster, I moved on to gold paint as I was obviously not the deft period artisan needed to apply the gilding.

Once the head was attached and liberally applied with gilding, I outlined the eyes in kohl,

then added faux glass “rubies” were glued into the eye sockets.

Feathers were attached to the head for a crest.

This gives the overall presentation a richer, more finished look and I believe closer to a period cooked peacock.

Finally the time had come to sew the skin onto the form. This presented a new problem. The skin was not the full skin of a peacock, just the neck, back with wings and the tail. I had not noticed this detail till I put the skin over the peacock form.

This means the form, I had ready for the skin to be stitched onto, was too large and the skin to small. This left me with several bad options. The first would have been to not use the form and just lay the skin out as a side note. I did not like this idea as it lacked grace and style. The second was to form a cloth covering to which the skin might be sewn onto then having the cloth covering sewn onto the form. I attempted this, going so far as to actually making a body covering drape pattern. The third idea, which is the one I went with, was to ribbon the skin and tie it to the body form. This idea presented the best idea overall as the form can be arranged then have the skin draped with minimal damage to the skin and feathers while shifting from one angle to the next on display

Once I realized I could not fit the skin over the peacock form, my plan was to sew ribbon on to the skin to form a tied collar. Unfortunately the way the skin was cured, it has started to flake and tear along stress lines making sewing impossible. I attached ribbon to the neck via glue. Not period glue but glue none the less.

This affixed the ribbon while stabilizing the stress areas along the neck of the skin.

Once the ribbons were attached I sewed on metal tippets with faux pearls.

This is non-standard; however as this display, if the standard recipe had been achievable would have been served on the high table, the idea is to make the overall look as rich and elegant as possible. The peacock is now painted, dressed and ready for displaying.

Recipes:

The edibility of the flesh of a peacock varied from cook to cook. Scappi, cook for the Popes of Rome in the 1500s, is quoted on peacock taste as saying, “[t]heir flesh is black, but more tasty then all other fowl.” (pp. 206). Augustine conducted experiments on the antiseptic quality of peacock flesh. He found that the flesh shriveled but did not rot. (Sparknotes/ bestiary). Medieval bestiary states “the flesh of a peacock is so hard that it does not rot, and can hardly be cooked in fire or digested by the liver…” (bestiary) Even with such unenthusiastic endorsements, this did not stop the consumption of this fantastic fowl.

Roman Recipes –

“Some times the peacock…were roasted then had their plumage restored to them…to prepare a bird in this fashion, take off the feathers with the skin. Cure the skin with coarse sea salt, so that it dries out a little, and wash it off just before you dress the roast bird in it…” (Faas, pp. 297).

On a side note, the peacock was so expensive (roughly 50 denarii a bird) that some peacocks were stripped of their skin then cooked (roasted) in aromatic resinous substances until the meat was effectively mummified. Afterwards it was redressed and reserved at another banquet later that week or month without fear of rotting. (Toussaint-Samat, pp. 38)

Another great recipe was…

“Grind chopped meat with the center of fine white bread that has been soaked in wine. Grind together pepper, garum and pitted myrtle berries if desired. Form small patties, putting in pine nuts and pepper. Wrap in omentum and cook slowly in caroenum.” (Giacosa, pp. 90)

The ground meat patties of peacock have first place, if they are fried so that they remain tender… (Apicius, 54/Giacosa, pp. 90). This recipe, for ground patties, was probably used for peahens past their reproductive cycle, and at 50 denarii per bird, this would still be a very expensive and luxuriant dish to serve to nobility and emperors.

French Recipes –

Peacock/Swan “Kill it like goose, leave the head and tail, lard or bard it, roast it golden, and it with fine salt. It lasts at least a month after it is cooked. If it becomes mouldy on top, remove the mould and you will find it white, good and solid underneath.” (Taillevent, pp. 23)

Reclothed Swan (substituting Peacock) “…in its skin with all the feathers. Take it and split it between the shoulders, and cut it along the stomach; then take off the skin from the neck cut at the shoulders, holding the body by the feet; then put it on the spit, and skewer it and gild it. And when it is cooked, it must be reclothed in its skin and let the neck be nice and straight or flat; and let it be eaten with yellow pepper. (Goodman, M-30)

Italian Recipes –

“if you want to roast a peacock on a spit, get an old one between October and February. After it has been killed let it hang for eight days without plucking it and without drawing it; then pluck it dry…When it is plucked draw it…..put one end of a hot iron bar into the carcass through the hole by which it was eviscerated being careful not to touch the flesh: that is done to remove its moistness and bad smell. To stuff it use the mixture outlined in Recipe 115, or else sprinkle it with salt, fennel flour, pepper, cloves and cinnamon; into the carcass put panicles of dry fennel and pieces of pork fat that is not rancid, studded with whole cloves or whole pieces of fine saveloy. Blanch it in water or sear it on the coals. Stud the breast with whole cloves. (The breast can also be larded or wrapped in slice of pork fat as is done with the pheasant in Recipe 135). Roast it over a low fire, preserving the neck with its feathers as is done with the pheasant. Serve it hot or cold as you wish, with various sauces …(Scappi, pp. 207)

The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi, recipe #139 suggested for pheasant or peacock.

“If you want to roast the small ones on a spit, as soon as they are caught pluck them dry and draw them; leave their head and feet on. Stuff them with a little beaten pork fat, fresh fennel, beaten common herbs, raw egg yolks and common spices – which is done to keep them from drying out. Sew up the hole and arrange their wings and thighs so they are snug. Sear them on coals. Wrap them, sprinkled with salt and cloves, in a calf or wether caul, or else in slices of pork fat with paper around them…When they are done serve them hot. (Scappi, pp. 206)

English Recipes –

“Take a peacock, break his neck, and cut his throat, and flay him. The skin and the feathers together, and the head still to the skin of the neck, and keep the skin and the feathers whole together; draw him as a hen, and keep the bone to the neck whole, and roast him, and set the bone of the neck above the broach (spit), as he was wont to sit alive; and above the legs to the body, as he was wont to sit alive; and when he is roasted enough take him off, and let him cool; and then wind the skin with the feathers and tail about the body, and serve him forth as he were alive; or else pluck him clean and roast him, and serve him as though do a hen. (Renfrow, pp. 572).

“Take and flay off the skin with feathers and tail, leaving the neck and crest still upon the bird, and preserving the glory of his crest from injury when roasting by wrapping it in a linen bandage. Then take the skin with all the feathers upon it and spread it out on the table and sprinkle thereon ground cinnamon. Now roast the peacocke and endore him with the yolkes of many eggs, and when he is roasted remove him from the fire and let him cool for awhile. Then take and sew him again into his skin and all his feathers, and remove the bandage from his crest. Brush the feathers carefully and dust upon them and his comb gilding to enhance his beauty. After a while, set him upon a golden platter, garnish with rosemary and other green leaves, and serve him forthwith as if he were alive and with great ceremony.” (Craig, pp. 157)

“A peacock may also have the skin and feathers removed as described above when it may be stuffed with spices and sweet herbs, and finely chopped savory meats, and roasted as described in the foregoing recipe. Then replace the skin and feathers when it should be “served…”…with the tail of the peacock was covered with leaf of gold, and a piece of cotton dipped in spirits was put in its beak. This was set fire to as the bird was brought in Royal procession to the table with musical honours.” (Craig, pp. 157-158)

The Elements in Common:

Each of these recipes discusses the various ways in which the peacock could be cooked. Peacock, other than the Roman mummification recipe, mostly dealt with removing the skin with feathers, then roasting the meat. After removal of the skin with feathers on, it was laid to the side and sprinkled with either salt or cinnamon for drying out and, unbeknownst at the time, bacterial retardation that could cause food poisoning.

In several of the recipes the bird is larded or wrapped in bacon, to preserve the moisture of the meat due to the low fat content of the flesh, with various herbs along with bacon and eggs used for stuffing. This would produce a more robust flavoring with lots of added fat content and juices.

Only one recipe (Roman) actually suggests grinding the meat into patties for frying and not serving whole. Further research shows that the recipe for ground poultry meat has spices and nuts mixed in before frying into patties. As the male peafowl was valued for their brilliant feathers, I wonder if this recipe was used on peahens that had out lived their egg laying/brooding days.

Two recipes suggest using other types of meat to stuff the skin back into the form of the original bird with either savory meats such as pork and beef or the meat/bodies of small birds and herbs. This is a variation of “this is not the bird you think it is.” subtlety seen at grand banquets where the flesh of one animal or multiple animals or fowl were shaped or sculpted into the form of another. (Faas, pp. 68)

Ingredients:

Peacock (or edible bird substitute)

4 egg yolks

1 fennel

1 ½ lbs of bacon (6-8 Bacon strips and ½ lb bacon pieces)

1/2 tbs salt

1 tsp cinnamon

1/2 tsp ground cloves

2 tbs flour

Or

1 peacock

1 cup ground bread crumbs

1 tsp ground pepper

½ red wine (pinot)

1 tsb fish sauce

½ cup pine nuts

½ lb bacon

Or

1 peacock

2 lbs bacon

Salt to taste

Redactions:

Prepping:

Before any cooking of the duck can be done, the bacon has to be made. My research turned up little in the actual making of bacon. Bacon use is ubiquitous in a variety of cultures as an edible tasty larding or just wonderful tasty addition to any recipe. The making seems to have been so common that recipes for making were deemed unnecessary. You just knew how to make bacon. With that being said, I am using the wonderful research done by Sir Master Gunther and his bacon making class. I chose the French style for my experimentation in this new pork medium. However my attempt to make bacon did not yield enough quality bacon to use for this display. The bacon was too salty and I could not get the slices thin enough to actually wrap around a duck.

The slices were either chunks or short thin slices. Not much in between. I believe I will need to work on the recipe and slicing technique before I can use my own home made bacon. Loved the research Sir Master Gunther did, will definitely have another go at making bacon another time!

Italian Peacock #1

For the fennel stuffed duck the majority of prep work is getting the stuffing made. First I gathered all the spices together.

The bacon and fennel were cut into small pieces, with the egg yolk and spices added next.

Everything was mixed together as evenly as possible coating the fennel and bacon with the finer spices and egg yolk.

The young duck, without neck or head attachment,

was skinned ready for stuffing. Yes this gets very messy!

The mixture was then stuffed into the duck.

The duck after being stuffed was wrapped in bacon slices. I had to affix the bacon with skewers. Toothpicks would have worked; however I was out of those.

This duck is not being suggestive, merely showing all the yummy stuff just waiting to happen.

The duck was then placed on a rack in the oven for an hour and a half.

This is a very tasty way to eat duck. The bacon and fennel contemplate each other with the egg yolks. The skewers were determined to stay in, more then I was willing to yank the cooked duck apart.

I have done this recipe using ducks with their heads.

The duck can be “formed” to have an upright look using skewers down the throat and pinning the neck to the chest.

This method is messy and irritating. I preferred cooking without the neck and head attached. However I know realize why and how the metal skewers were used for maximum effect when cooking peacocks. Bamboo or even wooden skewers do not curve or bend in natural ways to get the best effect

This duck just looks very unhappy and not nearly as appealing as the non-headed duck dish. In period, as previously described, the eyes would have been replaced with something nicer like rubies.

Roman Peacock #2

Here, after gathering the spices together in one spot,

Pour about 1/3 of the wine into the bread crumbs and grind up the pepper corns.

I took the lovely dark duck meat,

stripped the meat from the bones, including some skin and fat then ground everything together.

This is one duck’s worth of meat in a Cuisenaire. Roughly about four maybe five cups worth of meat.

The duck meat is ground fairly fine with this method. In period, Romans would use a mortar and pestle for pounding their meat for dishes such as this. (Faas, pp. 135)

The meat was then combined with the spices, pine nuts, and garum. Next spices and breadcrumbs with wine were mixed with the ground duck, looking to overspill the bowl.

This may look like period meatloaf but this is forming into something so much tastier and will never need ketchup.

I formed small patties, roughly about the size of my palm. These will be very rich, so do not make them full sized.

The next step was to wrapped the patties in bacon instead of pork caul as no pork caul was to be had at any of my usual meat shops. This being the case bacon makes a good secondary choice.

Duck meat patty was placed on bacon, and then wrapped in the bacon in the start of something very tasty.

Next the duck patties were placed in the cooking dish that had been prepped with wine in the individual “cups”.

Next came the patties for cooking.

These were then slow cooked in a sweet red wine. Till the bacon was crisp and the duck well cooked.

After trying one of the “extras”, I have to say I really love this recipe. This has to be one of my favorite Roman dishes now.

A closer look at a cooked bacon wrapped duck patty.

The fat to meat ratio was as close to 80/20 as I could using only some of the skin and only a little of the fat stripped from the body. The meat to fat ratio, I have read on a couple of cooking websites to be the ideal for both flavor and the happy mouth feel for rich meat.

Roman meat was pounded for a ground meat instead of cut/chopped (Giacosa/Faas) as we do in modern day. Lacking a bevy of kitchen slaves or servants, I have chosen to use the modern day equivalent called a food processor. After the meat reached a chopped state, I incorporated spices, bread crumbs, wine and nuts. The mixture was formed into patties and fried in olive oil.

I felt that while this was not a dish which would have been redressed in its own skin, the taste is worth trying as another alternative to the manifold roast recipes. In my opinion, this dish likely came about when a peahen was past her prime laying stage and the Roman owner did not want to let the bird go to waste. Since the peahen is rather drab in comparison to her more colorful counterpart, she would not have been mummified and displayed, but the meat would never be wasted.

French Peacock #3

This was the simplest of the three dishes. The duck was stripped of its skin and salted, then wrapped in bacon.

This is to show how the duck is laid out then wrapped. I hadn’t actually gotten to the stripping of the skin. One of those “Ooops!” photos. Strip skin then lay naked duck on bacon, not lay duck on bacon then strip off skin. Things just get messy at that point!

This is to show how the duck is laid out then wrapped. I hadn’t actually gotten to the stripping of the skin. One of those “Ooops!” photos. Strip skin then lay naked duck on bacon, not lay duck on bacon then strip off skin. Things just get messy at that point!

Once the bird had been redressed in a pork covering, it was roasted for an hour or more, until done.

This style of faux “peacock” does not match the taste of the other two dishes. A skin covering would definitely needed to dress this bird up. The taste is excellent and easier to cook though I would say the taste is not quite up to par with the other two dishes.

Period vs. Modern Techniques:

If a peacock were to be redressed in its own skin and served there were a few steps that were done. In period a cook would have gone down to the market, Roman, Italian or English (if not to the livestock area where the fowl were hanging out) and purchased a bird of quality with feathers. The purchase, like today would have been a princely sum. The bird would then have been carefully skinned, with the skin being set aside and either salted or heavily sprinkled with cinnamon. (Renfrow, pp. 572/Faas. Pp. 297) The body would have had iron skewers inserted into the body to give the proper curvatures while roasting on a spit. (Scappi, pp. 207). Once the body had finished cooking, the beak, feet and neck were gilded with gold or a flour paste colored with saffron. (Craig, pp. 157). This is if the bird were to be served whole as a main display.

Other recipes called for roasting either in an oven or a spit, Sometimes even ground and formed into patties. (Faas/Craig/Scappie/Renfrow) This noble fowl was not just a one trick show peacock.

Modernly, I had to improvise throughout the whole cooking process. The first issue being I could not get my hands on a reasonably priced peacock fully grown with feathers. This required a substituted bird of good flavor and modest pricing. Duck to the rescue! Using store bought duck (not even the farmer markets in Austin carried ducks with skin and feathers attached). Next not having a spit or a wood fired oven, I had to resort to a gas powered oven. The no neck and head negated the need for spits though I have used wooden skewers in test cooking to give the ducks with heads a more lively appearance. They came out of the oven, not smiling…more screaming as the muscles around their mouth contracted opening their beaks and causing the tongue to extrude. At this point I decided that was far more realistic then any one should have to see and attempt to eat and went for the headless option. In period, I am sure the peacock’s beak would have been wound shut with wire or strong linen threads.

The body display differences came from not having a fresh peacock skin but one that had been preserved for display. The skin I had purchased was not a full skin, just the back and wings with only partial neck. This negated any attempted to actually dress up a duck like a peacock. The preserved skin would have been damaged and the duck would have tasted horrible! Instead I decided to enlist a description of how Romans found the peacock display a beautiful center piece. So much so that they would mummify the bird and the “handlers” would take the bird from banquet to banquet as a non-edible center piece. (Toussaint-Samat, pp. 38) I purchased body parts in plastic molding. In period a mold would have been carved from wood, possibly wax or even stone (though to be honest they might have rented the mummified bird instead of throwing a skin over a form as quicker and cheaper. I say this after having built, glued and gilded one preformed form). The gilding I have is in sheets of non-edible gild (a cost issue of faux gold vs. real gold). I could have used the period flour and saffron. Yet neither my faux gild nor the flour faux gild sheets looked good. So I went with the faux gold paint. There was gold gild paint seen in manuscripts, again a cost issue if I had been able to buy the real gold gild, hence faux gold gild.

The actual food ingredients were as period as possible i.e. organic where possible. The dishes used to cook the birds in were as period as possible in ceramic/pottery roasting dishes.

To have done this in a truly period manner, I would have needed to access to a market with peacocks in season, raise my own bird(s), have a wood fired oven. The metal spits could have been optional depending on which recipe I decided to serve. Modern substitutes were done when period items could not be obtained.

Conclusion:

This work represents a desire to attempt an in period impressive dinner subtlety, something that is not seen at most feasts in the modern world. I spent more time attempting to find peacocks at a reasonable price and already slaughtered, than revising my ideas to a more modest approach of buying a skin and working from a different angle with an affordable dark meat bird.

What I have found is that unlike a stuffed Boar’s Head, peacocks are hard to find at a reasonable price and buying just a skin whole or partial is still pricy and difficult to find. Once purchased, a live bird would need a very strong coop to keep out the opossums, raccoons and foxes that roam my back yard, which I do not own, as well as feed… The final hurdle in purchasing a live bird was that while I could have purchased the bird to skin and dress, I lack even the most basic skills that would have been necessary to skin and dress a bird in period fashion.

While this project was not as time intensive in the area of cooking as building a period castle subtlety, the search for an acceptable meat, again within price range, took several mental gear shifts.

I have enjoyed almost every step, immersing myself in the various techniques for raising, cooking and dressing a peacock in various period ways. This project has given me both great enjoyment and horrifying nightmares. I am not sure if I would attempt this again. I think I would want to wait another year to forget about some of the more harrowing minute details that were overlooked, unexpected or completely out of left field. I would have to say this project is not for the faint of heart. Each person has to know their limitations ability wise, in and out of the kitchen. I feel that I have risen to the challenge for a rare cooking research project in both perspective and display.

References:

Craig, E., (1953). English Royal Cookbook. Andre Deutsch Limited, London.

Damerow, G., (2010). Raising Chickens. Storey Publishing.

Fass, P., (1994). Around the Roman Table. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. 1994.

Giacosa, I., (1994). A taste of Ancient Rome. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Good man of Paris.(1395). Le Managier De Paris.

Refrow, C., (1998). Take a Thousand Eggs or More.

Scappi, B., (2008). The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570). University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2008.

Taillevent. (1989) le Viandier de Taillevent. 14th Century Cookery. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data.

Toussaint-Samat, M., (1992). History of Food. Barns & Noble Inc.

The Viandier of Taillevent , ed. Terence Scully,(University of Ottawa Press, 1988). As present by http://www.reference.com/browse/subtlety and by Patrick Martins, nyu

http://www.angelfire.com/mi4/polcrt/Peacocks.html

http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast257.htm

http://www.khandro.net/animal_bird_peacock.htm

http://www.peacockday.com/peahens.html

http://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/augustine/section2.rhtml

http://thecoolchickenreturns.blogspot.com/2006/05/chickens-in-ancient-rome.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peacock

APPENDIX I

Peacock Breed Information.

The Indian peafowl is a part of the pheasant family with the Latin name Pavo Crisatus. They are native to Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, and the Himalayas where they are considered an ornamental bird and not wild or a game type of bird. (anglefire.com). The Indian peafowl has iridescent green or blue-green colored plumage and an upright crest. There is also the Green Peafowl, Pavo Muticus, that ranges from Burma to Java. There is also the Congo Peafowl, Afropavo Congensis. (Wikipedia). White peafowl do occur in nature but are rarely seen due to lack of survival coloration. (peacockday.com)

This august bird traveled from India to the Middle East, from Alexandria to Greece and Rome. From the Mediterranean the peafowl traveled upwards into Europe. (anglefire) Here the bird was reared and considered not a game bird, even though it was imported, rather a domesticated fowl that went straight to the lords table. (Toussaint-Samat, pp. 83)

The peacock, unlike the chicken, was not a common bird. (thecoolchickenreturns.com) Unlike the chicken a peahen will only lay 3-9 eggs a year while a single chicken could lay up to 200 eggs each year. (Damerow). This cuts down on the number of chicks born and raised to maturity in any given clutch or year. Low numbers with great beauty, much like gold or rubies, raises the price of the peacock out of the common man’s reach. This scarcity of peacocks, caused the pricing to be such that only nobility could afford such a rare beauty for their yard or table. This holds true in modern times as well. The peacock is, to this day, raised sparingly and only by dedicated lovers and breeders of this beautiful bird, raising the price beyond the grasp of the casual observer.

APPENDIX II

An Historic Overview.

There are various mythologies associated with the peacock. Such myths include stories of their magnificent round tails with the many seeing “eyes” for the Greek goddess Hera. There were myths about the peacock and the Roman Goddess Juno as well as the guardians of paradise from Islamic folklore. (anglefire)

http://www.khandro.net/animal_bird_peacock.htm

Several other mythic symbolisms are the psychic duality of man with peacocks standing on either side of the tree of life for the Persians. Peacocks represented in Christianity’s mythos of the soul in Medieval Europe as immortality and incorruptibility to some sects. (Khandro)